Critics Complaining That ‘Leaving Neverland’ Is Too One-Sided Miss the Film’s Point

This week, HBO released the four-hour documentary film Leaving Neverland, which details the stories of two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, who survived childhood sexual abuse at the hands of Michael Jackson. The film is made up of deeply disturbing interviews interspersed with footage of Jackson and his properties, home videos and photographs of the boys, and footage of their public appearances. At its core, though, the film is four hours spent in the room with its four subjects: Safechuck, Robson, and their mothers. It is a film that tells four people’s stories, and while it has already had intense public impact, it makes no attempt to reach beyond the confines of its subjects’ personal experience.

For these reasons, the film has already drawn criticism from commentators of all stripes; Entertainment Weekly called it “woefully one-sided” and Slate staff writer Christina Cauterucci criticized the singular focus of the film, claiming it does a “disservice” to Safechuck and Robson by failing to mount a stronger defense of their claims.

But that’s the thing: the film isn’t a defense, and its subjects aren’t making “claims” so much as they are sharing their experiences. Those experiences are certainly harrowing, and have been and will be subject to litigation and public outcry, but ultimately, Leaving Neverland is a film, not a court case. And, though I can’t believe I have to do this, I’m going to explain why that’s okay.

We Americans have a standard of evidence that is both very specific, and quite vague. Any contribution to our public discourse seems to require rigorous, legal-grade proof in order to justify its existence. News must come in a certain format: “this is what happened, and this is how we know.” Hard evidence is the only evidence. Yet this expectation, while sound in theory, ends up leading to a lot of mistaken impressions. The problem is that the format creates an illusion of soundness. You can say “ice is frozen water, and I know this because of the following scientific observations.” But you can also say, “Trump did not collude with Russia, and I know this because Trump said so.” Both sound like rational, evidence-based reasoning, but one is a conclusion based on empirical evidence and the other is a falsehood based on an emotional appeal to authority. And, even more bafflingly, you can learn a lot more about a person and about the state of our nation from the latter statement than from the former.

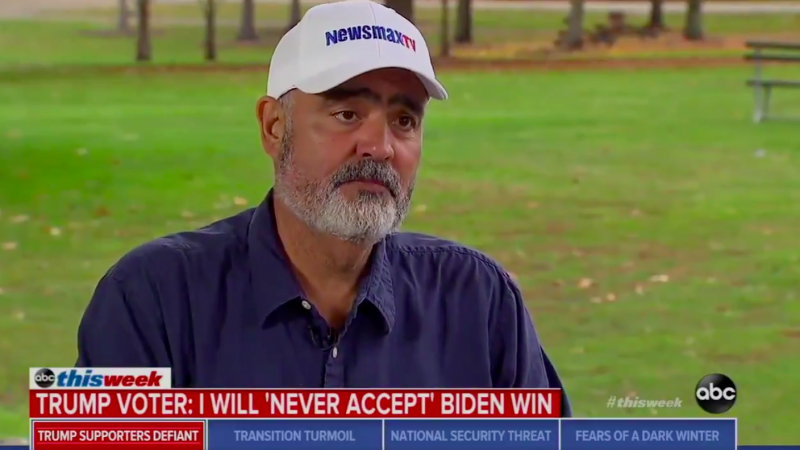

This attests to the fact that, even if it were possible for all supposedly “logical” arguments to be trustworthy[1], there would still be types of information that could not be expressed through them. A Trump supporter can lay out what he believes are the facts that support a Trump administration policy, but we learn just as much about him from the way he sneers at his opponent as we do from his actual argument. A bare outline of hard evidence can never contain all the facts.

To wit: a bare outline of who was at Michael Jackson’s ranch when, how rooms were arranged, and other disturbing details of Jackson’s interactions with the children he preyed upon, would tell one part of the story. That part is what would have been the focus of a fair trial, had Jackson ever faced one. But there were other factors at play: the social force of his celebrity, the suspect situations of his accusers’ parents, the testimony of frightened children he had groomed to lie for him, and the jury’s unwillingness to believe such horrors could be committed by such a beloved figure–that is, their unwillingness to believe they had been fooled. The bare statement, “the jury reviewed the evidence and found Jackson not guilty,” does not begin to tell the full story.

I’m not arguing that Leaving Neverland is a model for how a case should be made on an accuser’s behalf. Instead, I’m arguing that Leaving Neverland shouldn’t be asked to make a case. It is a moving record of the experiences of two boys and their families as Jackson’s predatory behavior insinuated itself into every aspect of their lives, and of the devastating aftermath. The film offers a different kind of evidence, and while it does contain statements of fact, it does not exist to carry those facts. Even if some of the film’s statements of fact prove to be incorrect, the film will still have mattered.

A friend recently remarked to me that, for abuse survivors, just to be heard, in full, without anyone questioning your veracity or motives, can be a profound kind of justice. That’s what Leaving Neverland offers: not a case against Michael Jackson, but a form of justice for two men whose stories were sidelined by the media circus surrounding the accusations. It is one kind of information that, resting alongside other information, begins to build a full picture.

This is part of what the #MeToo movement means for us as a society. The cry to believe survivors is not just a cry to support them with evidence, but also a cry for us to listen. To sit down and hear a survivor out is a small revolutionary act, and the fact that so many viewers of Leaving Neverland have proven willing to do it is a small victory that, hopefully, promises a larger turning of the tide.

— —

[1] Please do not mistake this for an argument that all truth is relative. That is certainly not the case. I only mean to demonstrate that it is easy to make a falsehood seem like a commonsensical truth.