Undertale Has Revolutionized The RPG

It’s bee n very hard to care about single player games with a narrative lately. The story that shambles alongside Diablo III was so devastatingly bad that, despite the fact that The Last of Us existed, I had lost an immeasurable sum of my hope in video game writing. Or more succinctly, I had resigned myself to a world where masterpieces like The Last of Us existed alongside dreck, much like Firefly must exist in the same universe as Full House.

n very hard to care about single player games with a narrative lately. The story that shambles alongside Diablo III was so devastatingly bad that, despite the fact that The Last of Us existed, I had lost an immeasurable sum of my hope in video game writing. Or more succinctly, I had resigned myself to a world where masterpieces like The Last of Us existed alongside dreck, much like Firefly must exist in the same universe as Full House.

Then I played Undertale. Holy shit.

The narrative power of Undertale is unbelievable, especially when you consider its apparently humble trappings. It is everything that gaming should be, and is quite possibly the strongest game in the jRPG genre that has ever been released, bar none.

Game Mechanics as Story in Undertale

This is probably a spoiler. Everything here, including the artwork, is probably a spoiler.

Menus

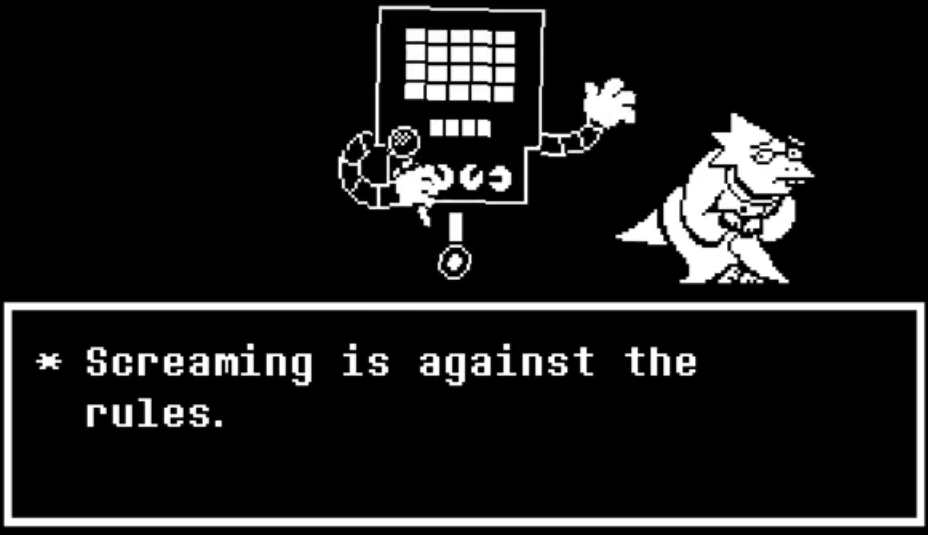

Undertale’s unique power–it’s DETERMINATION, if you will–comes from its integration of story and game mechanics. The bullet-storm minigame and on occasion, the very act of navigating the menu are integrated directly in the story. For instance, in a very important fight in the most common set of endings, the boss destroys the all-important MERCY button in the menu, forcing the fight to become a battle to the death. In another huge fight, in one of the less neutral endings, the bullet storm game turns into a sort of puzzle where one must use the in-game fighting avatar to physically reach the menu. And still in another memorable fight, the menu items are spit at you among the enemy’s projectiles, forcing you to make risky maneuvers or else not attack.

Undertale’s unique power–it’s DETERMINATION, if you will–comes from its integration of story and game mechanics. The bullet-storm minigame and on occasion, the very act of navigating the menu are integrated directly in the story. For instance, in a very important fight in the most common set of endings, the boss destroys the all-important MERCY button in the menu, forcing the fight to become a battle to the death. In another huge fight, in one of the less neutral endings, the bullet storm game turns into a sort of puzzle where one must use the in-game fighting avatar to physically reach the menu. And still in another memorable fight, the menu items are spit at you among the enemy’s projectiles, forcing you to make risky maneuvers or else not attack.

In other words, Toby Fox looked at his genre, said, “I have to have menus,” and then instead of accepting that there is only one way to incorporate menus, worked out a way for menus to be fun–while also making complete sense to his story. When King not-a-Mimiga physically and literally destroyed the “Mercy” option in the menus, my heart filled with genuine panic, followed immediately by sorrow. In a single, simple gesture that was built into very bones of the experience, without any dialogue, the game made me realize that I either had to kill a character I liked–or else die.

That’s power over the gamer you can’t buy, and Square-Enix would never have had to balls to put it in a game.

Triple A Gaming Kinda has a Point

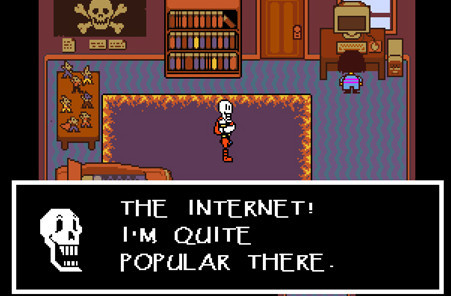

‘Course, there’s a reason a Triple-A company doesn’t make off-the-beaten-path games like this. Frankly, it’s inaccessible. It appeals to the Venn Diagram of players that result when three different, specific kinds of nerd exist in the same body. I sank into this game like a stone, but my roommate only warmed up to it when I wouldn’t shut up about it. And for a game with such a thin beam of appeal, it starts in a deliberately slow way. The first character you encounter literally holds your hand and drags you through the first puzzle, which is brilliant meta-commentary–but it’s incredibly possible that a player won’t realize that the game is working up to deep commentary on games–or that they won’t have played enough games for this sort of commentary to make sense. In either case, if the player gets frustrated because they lost control of their character at the first puzzle while a tutorial character solves it for them, it’s a very real possibility that they’ll shut the game off and go do something else. The graphics are already a huge turn-off for a lot of people, I suspect, and this is an erosion on the trust that the player has that they’re in good hands, so a slow start isn’t promising.

And while I absolutely adore the gameplay, it’s counter-intuitive. Challenges appear that the player was never mechanically prepared for, such as dodging Undyne’s spears, and that never repeat again. This didn’t phase me at all, but I’m watching one of my friends struggle to play past this verty zone–it’s frustrating and boring for her, and she’s given up progression for almost two days at this fight. The same thing happened to my girlfriend at a spider boss about mid-way through the game. Experimental gameplay and a narrow appeal is a downright dangerous move, so while I’d love to see companies like Square-Enix throw themselves into making games like Undertale, it won’t happen simply because they exist to distill games into pleasant blandness for the sake of pleasing as many people as possible.

Morality, Fighting, and The Bullet Storm

Every fight in Undertale can be fled from, or resolved peacefully, and the combat mechanic is interesting. Monsters fire magic at your soul, ala bullet hell games, and you smack their bodies with–well, whatever you manage to find. While some monsters are clearly out to hurt the player, others aren’t–but they still make the player dodge bullets. (This is disregarding Flowey’s Love Pellets. Absolutely pick those up.) The moral issue of whether or not you should kill these monster VERY quickly arises. In fact, the entire essence of the game’s narrative is built around the meta-morality issues of the JRPG custom of committing genocide via random encounters.

Every fight in Undertale can be fled from, or resolved peacefully, and the combat mechanic is interesting. Monsters fire magic at your soul, ala bullet hell games, and you smack their bodies with–well, whatever you manage to find. While some monsters are clearly out to hurt the player, others aren’t–but they still make the player dodge bullets. (This is disregarding Flowey’s Love Pellets. Absolutely pick those up.) The moral issue of whether or not you should kill these monster VERY quickly arises. In fact, the entire essence of the game’s narrative is built around the meta-morality issues of the JRPG custom of committing genocide via random encounters.

And it’s handled incredibly well. Random fight with a dog? Sure, kill it. Get some exp and gold. And now that dog will never be anywhere in the world again, and someone will probably chastise you for having killed it. Spare it, though? That’s where the joy of this game lies–that dog will be somewhere, later, building a snowman or a flipping a hamburger, and he will absolutely enrich the world. In fact, the “true pacifism” route through the game, wherein no experience or loot is ever earned from killing a monster and your equipped weapon is completely immaterial manages to be one of the richest, most rewarding experience, because the control you’re giving up over your character sheet is exchanged for a palpable control over the shape of the world.

(And spoiler–mishandle this, and you can become a monster.)

World Building

Every single detail in this game is laced with various levels of importance. Learn that a character is lazy and only reads car magazines? There’s a deeply meaningful reason waiting for you to find it. Learn that a certain monster likes being sung to? The act of learning this can subtly alter a fight later on. While the game is incredibly short, it not only rewards thorough exploration, investigation–and even meta-behavior, such as reloading fights to change the outcome, or actually waiting in an area when a character asked you to wait, rather than instantly leaving, as jRPG players are trained to do. This and the dozens of available endings, each one with deeply layered meaning that changes depending on what you have personally learned, reward repeated playthroughs in ways that no other game has ever managed. So while a dedicated jRPG player or a twitchy arcade game player can likely clear the game in five or six hours on a first play, there is easily 50 to 60 hours of gameplay in Undertale. For a $10 pricetag, this is a good deal. (And, in fact, the game addresses time-investment as a value measurement as a story issue directly, if you’re in the mood to have your understanding of stories in video games scrambled.)

Every single detail in this game is laced with various levels of importance. Learn that a character is lazy and only reads car magazines? There’s a deeply meaningful reason waiting for you to find it. Learn that a certain monster likes being sung to? The act of learning this can subtly alter a fight later on. While the game is incredibly short, it not only rewards thorough exploration, investigation–and even meta-behavior, such as reloading fights to change the outcome, or actually waiting in an area when a character asked you to wait, rather than instantly leaving, as jRPG players are trained to do. This and the dozens of available endings, each one with deeply layered meaning that changes depending on what you have personally learned, reward repeated playthroughs in ways that no other game has ever managed. So while a dedicated jRPG player or a twitchy arcade game player can likely clear the game in five or six hours on a first play, there is easily 50 to 60 hours of gameplay in Undertale. For a $10 pricetag, this is a good deal. (And, in fact, the game addresses time-investment as a value measurement as a story issue directly, if you’re in the mood to have your understanding of stories in video games scrambled.)

The result is that, despite the world being very small, it’s incredibly compact. This is the kale-esque superfood of gameworlds, simply because of the many ways it changes according to your actions. If the retro, off-beat graphics are a turn-off for you (they certainly were for me), consider that the trade off is entirely in developing the depth of the world. If the world is made of 2D sprites, you’re asking the player to do more of the world in their imagination. When the player is sharing some element of the creative load, then the developer has a lot more room to fill every nook and cranny, simply because it didn’t need to be modeled, rendered, and optimized. Ultimately, though, the graphics do their job. The quirky, cartoonish look they help cultivate hides the teeth of the story until it’s already on your neck.

And I loved every minute of it.