2020 Wishlist: The Romantic Action Epic Hollywood Is Ignoring

Greetings, gentle readers. This year, as we settle in for a new decade of escalating horrors, we reflect on what wonders the future may also bring. The 2010s brought us a television renaissance, a new Star Wars series (for our sins), and a new era of the superhero movie. As an antidote to the terrors of the roaring decade ahead, we’ve decided to create a wishlist for the movies and television we hope are coming. Let this be an island of optimism in a rising sea.

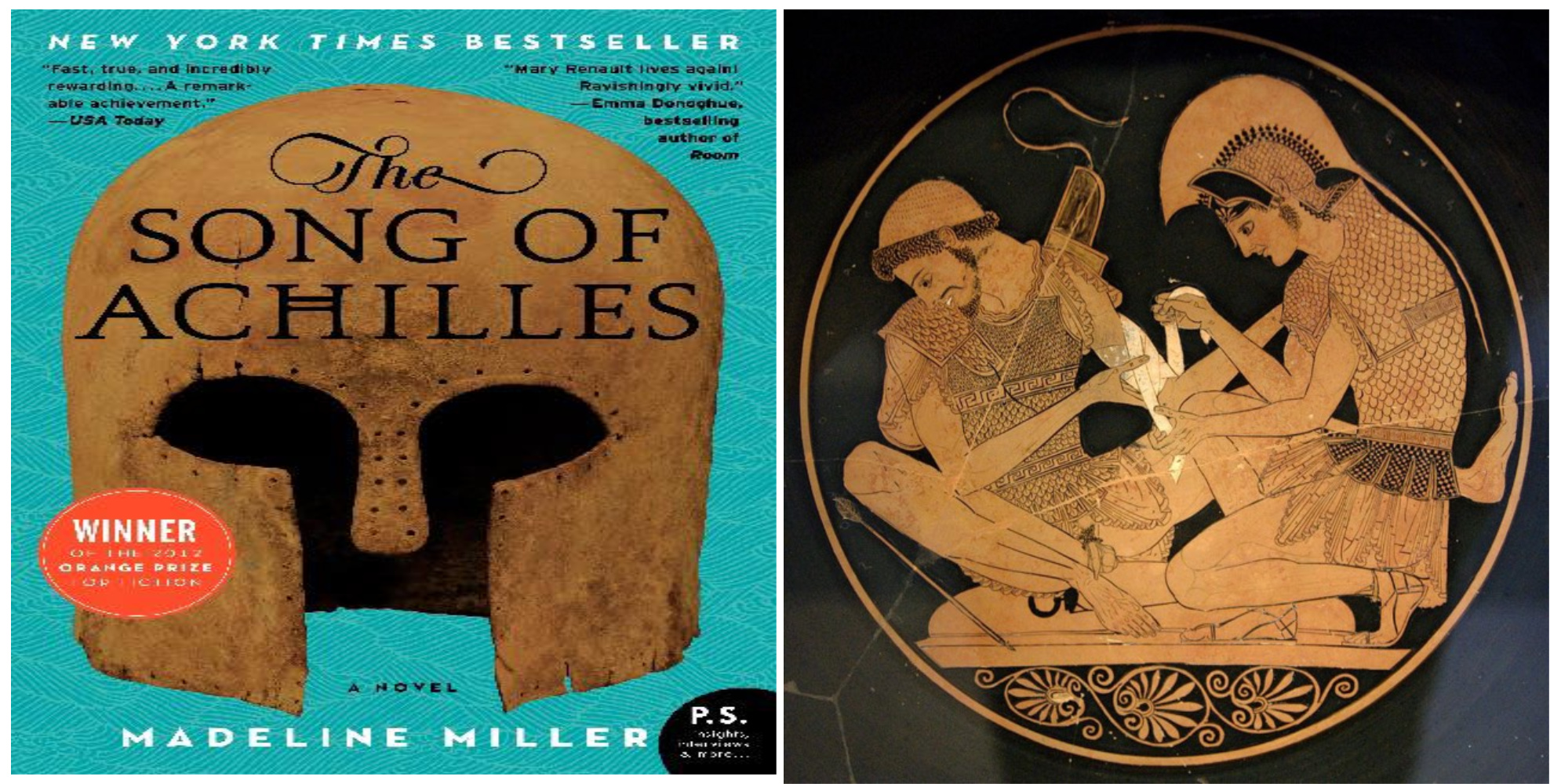

In 2012, one of the most satisfying, tearjerking, epic historical romance novels of all time came out. It has everything: war, interpersonal drama, redemptive love, tragedy, revenge — even centaurs and nymphs and ghosts! Blend The Lord of the Rings with The Notebook, and imagine that the authors of both of those had been significantly better writers* — have I sold you yet?

You might smugly be thinking, “well, surely if it’s that important, then I, a cultured individual, have already read the book.” Well, pal, I have news for you: if you’ve read this one, you’re probably either gay, a close friend or family member of a gay person, or an actual classics professor. Because the book I’m talking about is Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles, and the romance is between the legendary warriors Achilles and Patroclus.

Before I get into the reasons a Song of Achilles movie would be the perfect apology for 2004’s Troy, for which Hollywood should long since have personally apologized to each and every American, a brief note on the mythology. If you haven’t read this novel or recently finished a college literature class, you probably don’t remember who Patroclus was. If you do, skip the following paragraph.

Perhaps you remember these elements from the plot of Homer’s Iliad or some other tale of the Trojan War you may have encountered: Achilles, a demigod warrior blessed with physical invulnerability everywhere except in his heels, goes with the greatest fighters in Greece to lay seige upon the city of Troy (for stupid mythological reasons). He is under a prophecy that, if he fights, the Greeks will win, but if he kills the Trojan Prince Hector, his own death will follow. So, despite being the only one strong enough to defeat Troy’s greatest warrior, he lets the war drag on for a decade. Agamemnon, essentially a Greek general, offends Achilles by stealing an enslaved Trojan woman from him (because ancient Greek culture was actually awful), and in a fit of pique Achilles announces he will not fight until the slave, Briseis, is returned. This is all well and good until the Trojans get unusually daring and decide to attack the Greek camp and burn their ships. Fearing they will actually lose the war, Achilles’ boyfriend Patroclus, an honorable man but a poor fighter, resolves to put on Achilles’ armor and ride into battle to frighten the Trojans into retreating. He can’t fight like Achilles, of course, and as soon as the Trojans catch on to this, he’s done for. Hector kills Patroclus, and Achilles is inconsolable. He throws aside any fear of the prophecy and challenges Hector to single combat, killing him. While Hector’s death is the beginning of the end for Troy, which will soon be sacked thanks to the famous horse, it also seals Achilles’ fate; Hector’s brother Paris gets revenge by shooting Achilles in his one vulnerable spot, his heel.

That’s not just the plot of The Song of Achilles, my friends. What I’ve just described is the actual, literal plot of the Iliad. While the Homer text, at least according to Miller, never goes out of its way to point out that Achilles and Patroclus are lovers,** she tells us that other ancient writers, including Plato and Aeschylus, are not at all shy about it and seem to consider it an accepted fact of the story. The eagle-eyed bookworm will find oblique references to this agreed-on fact in works like Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida and Hugo’s Les Miserables. Even the great classicist Edith Hamilton, who as a gold-star lesbian in the early 20th century tended to be circumspect about these matters, has Achilles declare in her Mythology, “I will kill the destroyer of him I loved.” So, you know, no homo.

But Miller doesn’t just update the story of the Trojan War by putting into plain English the underlying assumptions that have guided readers of Homer for centuries. Her truly remarkable achievement is to shift our perspective on a famous story. She adapts the sweeping and impersonal genre of the epic into something we can comprehend via the intimate, psychologically complex storytelling conventions of the modern world. The love story between Achilles and Patroclus has always been at the heart of the tale of the Iliad. Homer might not have needed to remark on it for his audience to get the picture, but Miller does. The flip side of this is that, since scholars starting in the Victorian era decided to crack down on the Classics and crush all the queerness out of them (and the classics are almost entirely queer, so this was quite a project), readers have been astonished to find in Miller a love story that was taken for granted for most of the myth’s history. Thus, while it has only slowly gained mass attention, the novel has been a queer classic from the beginning.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about why this movie needs to happen. First off, while she is certainly a literary writer and her books stand on their own just fine, Miller’s writing is full of evocative images that will lend themselves beautifully to screen adaptation. That’s why her more recent novel, Circe, has already been claimed for an upcoming HBO miniseries. Miller notes in her announcement of this news that The Song of Achilles was optioned by the BBC in 2015, but that those rights have lapsed and the novel is once more up for grabs. What makes Circe so much more adaptable, while The Song of Achilles has been accumulating fans and critical acclaim for so much longer?

Well, Miller’s Circe is straight enough to watch all the Underworld movies in a row without once noticing Kate Beckinsale’s costume. That’s why.

But I promised myself I would present my queer agenda only as secondary reasoning for wanting to see this movie happen. Now let’s get back to my main point: we, as a society, deserve reparations for 2004’s Troy. With its inexplicably all-white cast, it tries to present Paris and Helen as being in love, kills off Agamemnon at the hands of Briseis (he’s supposed to sail home and be murdered by his wife, and without this event, important subsequent myths, such as Electra and the founding of Athenian democracy, are erased) and showcases exactly how far Orlando Bloom’s acting range doesn’t extend. But most damningly, it’s boring. It’s the most recent attempt to adapt a story of the Trojan War, and it’s boring.***

The Song of Achilles is not boring. It balances the private lives of its complex, relatable characters against the crushing weight of the war’s world-shattering stakes. Narrated by Patroclus, it gives us a strong, sensible Briseis, a fierce but sympathetic Thetis (Achilles’ nymph mother), and an Odysseus who is both charismatic and deeply dangerous. Most of all, it gives us a rounded Achilles, a golden boy who knows his value and is awash in hubris, but who is vulnerable to his love for Patroclus: a gentle boy who would rather heal than fight, but who will fight unerringly to honor the code he lives by. It shows us the emotional stakes and consequences of the war, not just its gory battles (though some of those are also depicted in exciting action sequences). There’s magic, there’s adventure, and the fates of kingdoms are moved, but there is never a moment of emotional distance. A movie version of The Song of Achilles will be both a beautiful spectacle and an intellectually and emotionally engaging drama. When was the last time Hollywood gave us a movie that achieved both those things?

— —

*Calm down. As a devoted Tolkien fan, (feel free to test me, Twitter; I know you will), I personally enjoy his ponderous, poetically repetitive, elaborately descriptive writing style. But Madeline Miller spins a better yarn, and if you don’t believe me, you haven’t read Madeline Miller.

**Other scholars seem to have different takes on what Homer’s text literally says, but since this author does not personally read ancient Greek, this author will defer to greater experts.

***Not counting a couple of dreadful TV series, of course.