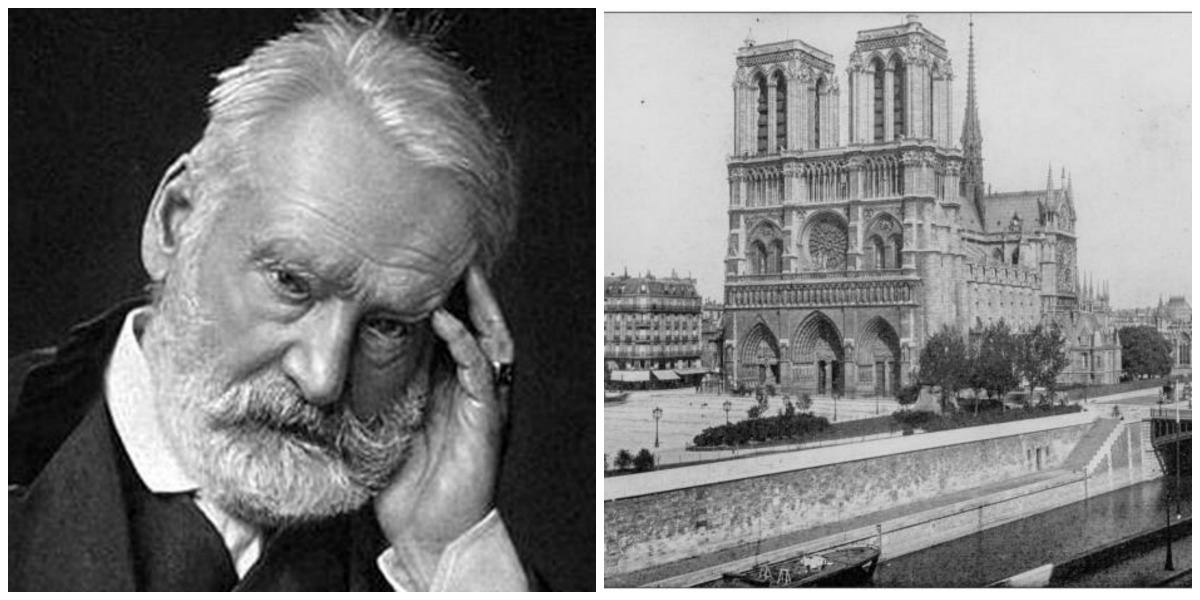

Victor Hugo May Be Dead, But He Is Still Notre Dame’s Chief Mourner

Today, Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral, one of the most iconic buildings in the world, caught fire and was partially destroyed. Its famous spire burned; its roof, a prime example of medieval architecture, is gone; and its exquisite stained glass windows are, according to officials, probably destroyed as well. The horror of this moment will forever mark a milestone in the lives of those who saw it.

We all, I think, would be hard-pressed to name anyone we know who was not deeply affected by this severe blow to art, history, and the Parisian community. But then, there are many (seen here and here), myself included, whose hearts went out to a man we do not know, because he has been dead for over a century.

Victor Hugo, one of France’s greatest writers, lived in the nineteenth century (1800s), and he loved Paris to his core. As a young writer, he was moved by the medieval gothic cathedrals that studded the city, and he was horrified by the state of decay many of them were in. He particularly loved a crumbling building called Notre Dame Cathedral, and its poor state of repair inspired him to write one of his most popular novels, Notre Dame de Paris, usually known in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Though best known today for its compelling characters–sweet ostracized Quasimodo, villainous Claude Frolo, fierce Esmerelda–the novel was, as critic Lindsay Ellis has remarked, more about the building and its history than it was about the people who moved through it. That, in Ellis’ opinion and in mine, is rather the point: human tragedies play out, but the structure still stands.

This was not, however, taken for granted in Hugo’s time. Historical preservation was not a priority in a Paris that was still recovering from the French Revolution and Napoleon’s subsequent reign. Hugo’s work, filled with Romantic-era pathos and nostalgia, swayed public opinion in favor of taking action to preserve France’s landmarks, Notre Dame in particular. In his preface to the novel, Hugo describes a bit of graffiti, probably medieval in origin, scratched into the stone: the Greek word Ananke, the name of a goddess who represented the inevitable force of fate. When Hugo returned, later, he said, the word had been scrubbed away:

with the exception of the fragile memory which the author of this book here consecrates to it, there remains to-day nothing whatever of the mysterious word engraved within the gloomy tower of Notre-Dame,—nothing of the destiny which it so sadly summed up. The man who wrote that word upon the wall disappeared from the midst of the generations of man many centuries ago; the word, in its turn, has been effaced from the wall of the church; the church will, perhaps, itself soon disappear from the face of the earth.

Hugo thought that this disappearance would proceed from negligence on the part of people who did not understand Notre Dame’s value; while that is not the case today, it is clear enough that Victor Hugo, were he alive to see today’s fire, would have been foremost amongst its mourners.

Hugo’s work to promote the preservation of Notre Dame was not in vain; because of his efforts, millions of people who might not otherwise have seen Notre Dame were able to enjoy its beauty. This does not, however, make it easier for any of us to reconcile with the fact that future generations will never experience the Notre Dame we have known.

The burning of Notre Dame is not an attack. There is no discernable evidence of malice on the part of whoever started the fire; it was probably a construction accident. It makes the event difficult to process: it seems, at first, that we learn nothing from this event except that the force of Ananke is irresistible. That’s not the whole story, though.

The story also includes the four hundred Paris firefighters who unhesitantly risked their lives in their dedication to preserving Notre Dame and its artifacts. It includes the Parisian citizens who gathered to sing hymns and pray as they watched the cathedral burn. In the same way that the human story of Notre Dame de Paris has overtaken its tragic origins, the human story of the cathedral’s real-life destruction is a bud of hope in the face of an irrepressible tragedy.