A Short History Of The ‘Bambi’ Vegetarian

At dinner with my mother one night, I asked what her favorite Disney movie was. Everyone in my generation has a quick answer to this (I say Aladdin if I’m with someone I don’t need to impress, and Sword in the Stone if I need to look clever). My mother, however, didn’t. She paused, took a sip of her wine, and then surprised me.

“I guess Bambi. It was pretty influential for me.”

She had talked about Bambi before — she went vegetarian about a year before I was born, though she always avoided meat, and often cites the movie as part of her inspiration — but I never connected that with the concept of “favorite.” For people who grew up watching Bambi, (which is most Americans currently living), the common assumption is that the death of Bambi’s mother is a traumatic moment better put out of one’s mind.

But it’s different for people like my mother. When she saw Bambi, she did not take away the generally accepted message that life is scary. What she saw was that animals are people, and we should treat them accordingly.

So my mother and I are Bambi vegetarians. Sure, we have a hundred justifications ready for when meat eaters doggedly interrogate our motives (and meat eaters love to do this): it’s better for the environment, it’s ethically sound, it’s good for your health, all that. But the core reason, the one that makes eating meat unimaginable to us, is emotional. We believe in animal personhood, and it hurts us to see animals in pain and afraid due to human encroachment on their lives.

Vegetarianism is much more prevalent in this country now than it was when I was growing up, and while plenty of people still do it out of empathy for animals, more and more go vegetarian or vegan for environmental or health reasons. I’m all for this — now that there’s such a thing as vegetarian fast food, I’m no longer inclined to question anyone’s motives — but it is worth noting. Now that there are so many vegetarians, there are types.

With all this in mind, we sat down recently to watch Bambi. It was the first time in years for all of us, so while we maintain a deep emotional attachment to the story and characters, there was also enough distance that we could see with fresh eyes.

Bambi, Disney’s fifth animated feature, was released in 1942, and you can tell. The musical score–mostly classical, balletic music, with the occasional swell of a tightly-harmonized chorus–is the biggest giveaway. More than that, though, the story hangs on the scaffolding of a rigid patriarchal structure in which male characters are separated from women and children. The film is presided over by Bambi’s father, the Prince of the Forest, distant and graceful on a precipice. I think the intention is for the audience to find this comforting.

But I’m not here to rant about the patriarchy (this time). I wanted to see what made this movie tick — and, in turn, why it had such a deep effect on my mother and myself. And what I found was that it’s not just an emotional movie with animal characters, but a cohesive argument for animal personhood.

The film opens with a montage depicting woodland life from the perspective of the animals. They bathe, socialize, eat breakfast. The animals in this film have their own concerns, their own lives. Not a single human is pictured on screen at any point in the film; the animals are the point-of-view characters.

The action of the story begins with an announcement of Bambi’s birth — a “new prince” of the forest. All sorts of creatures flock to see him curled against his mother’s side, sleeping to angelic music in a shaft of sunlight. Bambi and his mother are divine, the center of the woodland creatures’ world, and, while we’re watching, the center of our world as well.

As spring proceeds into summer, the little prince goes among the common people, learning the skills of life all the while. Thumper, a rabbit of Bambi’s generation, is a very vocal witness as Bambi takes his first steps, learns to navigate the forest, and learns to speak. When he is ready, Bambi’s mother takes him to the meadow, teaching him to enter the exposed area with great caution, before showing him to the feast of fresh grass. Bambi wanders until he happens on a pond, where he gazes on his reflection for the first time. It’s a short but important moment: he moves about, feints side to side, slowly coming to recognize that what he sees is not another fawn, but rather his own reflection.

It’s a sweet moment, but let’s take a quick detour into its scientific significance. What Bambi does here is pass the Mirror Self-Recognition Test (MSR), a test animal behaviorists use to determine whether a species is self-aware. Virginia Morell, the science writer whose work first introduced me to this concept, says that “animals that pass the MSR test are thought to belong to an exclusive club, one whose members can think about themselves and their actions” [1]. While the MSR test as a named scientific principle only dates back to 1970, Bambi’s self-recognition is still relevant to our discussion, both because modern audiences are aware of its significance to animal cognition, and because, even before it was used by animal behaviorists, recognition of one’s reflection was still seen as a notable developmental stage for human infants.

Almost the moment Bambi recognizes his own face in the pond, he is distracted by another reflection: that of Faline, the doe who will later become his mate. What follows is a charming chase scene that can’t quite cover the seed that has been planted in our minds. We have just been told, conclusively, that Bambi (and by extension all his family and woodland friends, who seem to be equal to him in intelligence) is sentient.

And then, mere moments later, the meadow is overtaken by the alarming colors and martial music of fall — hunting season. The deer flee the forest, and we are introduced to the villain of the piece.

“What happened, Mother?” Bambi asks once they are safe in the woods. “Why did we all run?”

“Man was in the forest,” she tells him, and makes no further comment.

After a miserable, hungry winter, Bambi and his mother return to the meadow in what must be late February or early March (outside of deer hunting season). They have just found the very first of the spring grass when the vital moment occurs: shots are heard, they run for the forest, and Bambi’s mother is gone.

It is in the deathly calm just after this catastrophe that Bambi’s father, the Prince of the Forest, speaks his first words in the film. He appears to the panicked, grieving Bambi, and says only, “Come, my son.” With that, Bambi’s childhood ends, and he follows his father to learn the art of being a stag.

Earlier in the movie, Bambi’s mother observes to him that his father is the Prince of the Forest because he is the eldest deer in the forest, having outlived the others of his generation and gained “wisdom” that is rare for their usually short-lived species. So the Prince of the Forest is taking Bambi away to teach him the art that confers true nobility: the art of survival. This frames the death of Bambi’s mother, traumatic as it is, as a necessity. If Bambi is to survive, he needs the strength that being forced into the realm of stags will give him.

It may seem like this is all beside the point — what can a ‘survival of the fittest’ narrative add to an argument in favor of vegetarianism? — but bear with me here. I just want to talk you through the movie’s ending, and then you’ll see where I’m going with this.

We skip to spring, when Bambi returns to his old stomping grounds, now a young stag with newly sprouting antlers of his own. He and his sidekicks, Thumper and Flower (the skunk), fall in love one after the other, and Bambi is reintroduced to Faline, whom he quickly chooses as his mate. He is curled up with her in his mother’s old glen when Man returns to the forest. This time, when they shoot, the hunters start a forest fire, and there is a mass exodus of woodland creatures. Bambi is separated from Faline and shot — where, it’s not clear, but possibly in the shoulder. He would be left for dead if not for his father, who encourages him to stand as he watches over him, in a grim echo of the moment at the beginning of the film wherein Bambi takes his first steps under his mother’s patient gaze. After some additional trials, Bambi is reunited with Faline, and the movie ends with the creatures of the forest gathering to see her twin children, while Bambi stands on a precipice with his father, looking proud. The cycle is complete: the Prince of the Forest still survives, and Bambi has become his heir apparent by learning to survive alongside him.

So how does a film whose story seems to underscore the inevitability of violence and death for creatures like Bambi, produce generations of bleeding-heart vegetarians? It’s all a matter of perspective. As I mentioned above, Bambi is a story told from the animals’ perspective. Humans are not pictured; they have no significance to the animals except as formless and faceless agents of destruction. Life — daily concerns, relationships, love, fear, and grief — is the sole realm of the animal characters, and while we are absorbed in the film, we know what they know and feel what they feel. And for these animals, survival is the highest of all values; they found the consummate survivor in their ranks and named him their Prince. While we are watching Bambi, we see animals as people, and we see their survival as valuable, even necessary.

Not everyone who sees Bambi takes this experience to heart. If they did, the meat industry would have failed long since. But for those of us who view Bambi with whole-hearted involvement, what we learn in that forest can never quite be shaken. We see animals for the complex creatures they are, and we value their survival. This is not a logical reason, like some of the others we may have for choosing not to eat meat, but it is a kind of divine message that will always resonate with us.

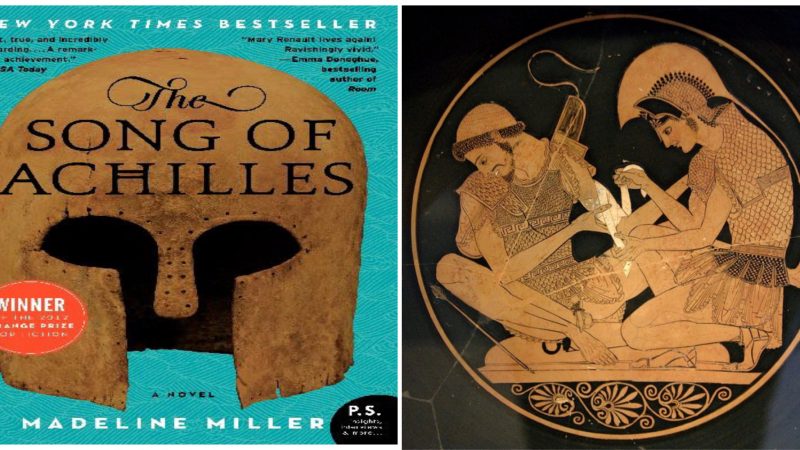

[image via screenshot]

Footnotes

[1] Virginia Morell, Animal Wise, p. 159. This 2013 book on animal cognition is a fascinating study that, in this humble author’s opinion, everyone should read.

Ms.Van Houten. I was so moved by your article. Born in 1951, I watched “Bambi” on a toy television that my mother bought, read the children’s book, but I don’t remember seeing it at the movie theater because they were segregated in the South. Your story mirrors my own feelings and reactions to man’s treatment of our animal family and as the years went by, I became a vegetarian. It was in the mid-70s. I was sitting on the corral fence. My horse and dogs gathered around to see what I was eating. Looking at them, it occurred to me that if I lived in a different country/culture, I might be eating them, instead. Dabbling with vegetarianism off and on, this realization touched my heart, embedding and changing me, 180 degrees.

Because of catastrophic occurrences in my life, I have dropped back into old needs to for nostalgia. But then the taste, texture, and knowing that the object on my plate once had a family, once freely roamed the earth as I do, turns me away. When I look into the eyes of my sheep, horses, and cats and I realize the relationship that we have is unlimited with each day providing a new fact would amaze me if it weren’t just normal. I am teaching them English and they are teaching me Ovine, Equine, and Feline. The way we work together amazes people and delights me.

Being an English teacher (retired and dealing with cancer), I am in relatively good health and I credit part of this with the change in my spirit living on this planet in more harmony with other living beings. With all the additives animals have to suffer with, it’s probable that ingesting these poor,contaminated creatures and knowing the truth in the saying, “You are what you eat” might have made this cancer more aggressive. What people eat today, especially children, makes me wonder what the future holds for them, for their health and mental acuity.

Thank you for your article. I hope other people will take time to tell their stories. I know how intelligent, sensitive, independent, thoughtful, cooperative… animals can be, often more so than many people. They deserve life.